Strategic Knowledge, State Purse: Why Area Studies Rise When Great Powers Expand

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The EduTimes editorial team, in collaboration with SIAI’s Global School of Business (GSB). While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

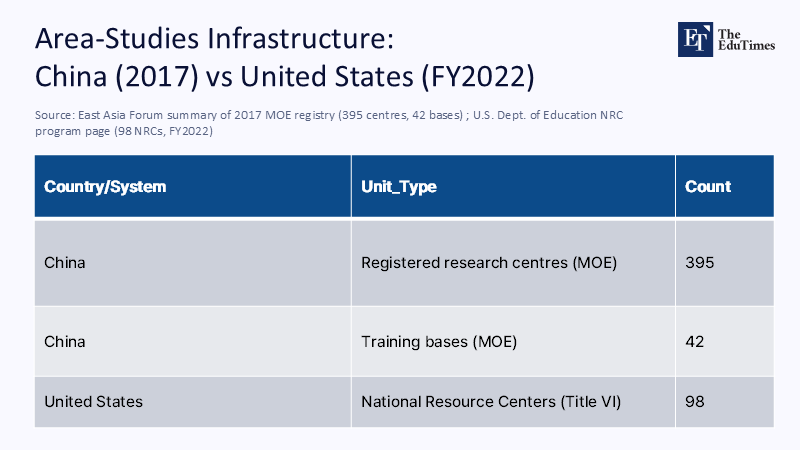

In 2017, China formally registered 395 university-affiliated research centers and 42 training facilities dedicated to what it terms “country and regional studies.” Five years later, in September 2022, this field was elevated to a first-level interdisciplinary discipline that grants degrees, a bureaucratic advancement that secures funding sources and faculty pathways. Meanwhile, during this same timeframe, the United States continued to support its Cold War–era frameworks, specifically Title VI programs, which have funded area and language expertise with annual investments of $75–86 million across National Resource Centers, Foreign Language and Area Studies fellowships, along with related initiatives. These two snapshots—China’s extensive registration and official elevation alongside the U.S.'s ongoing financial support—illustrate a straightforward reality that we have hesitated to acknowledge: area studies flourish when nations act like empires, as private markets typically do not invest in what is dictated solely by strategic interests. As policymakers, your role is not just to finance area knowledge, but to oversee it effectively without stifling scholarly pursuits.

From Subsidized Niche to Strategic Infrastructure

There has been a significant shift in the perception of area studies. Once considered a soft, underemployed mix of humanities and social sciences, it is now viewed as a strategic infrastructure. This transformation, driven by Chinese policy, has tasked area studies with 'serving national strategy' and supplying universities and ministries with targeted expertise. The upgrade in 2022, when area studies became a first-level discipline, marked a significant change. It moved from a curricular curiosity to a degree program with quota seats, promotion ladders, and budget lines. This shift is not accidental. Since Xi Jinping’s 2016 directive to 'accelerate the construction of philosophy and social sciences with Chinese characteristics,' universities have been pushed to align knowledge production with state priorities, including the Belt and Road and a more assertive foreign policy. Elevation brings resources—and supervision. The crucial point is not censorship per se but instrumentalization: states now see area knowledge as a mobilizable capability, like chips or shipyards, and they are building it accordingly.

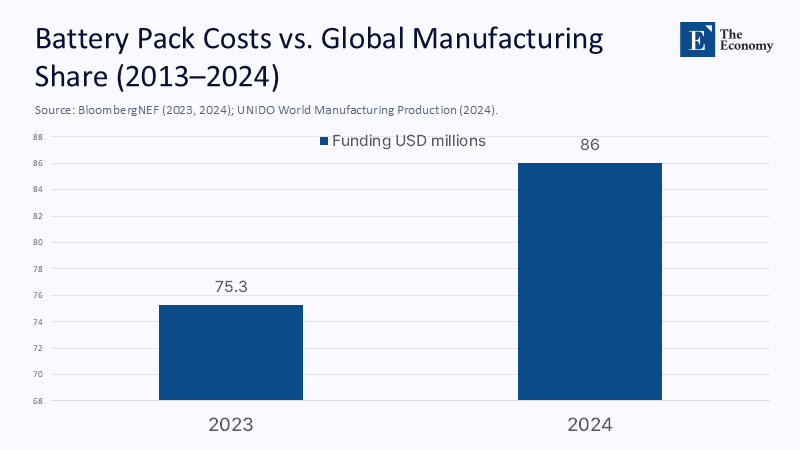

The United States is hardly exempt from strategic framing. Title VI was born as a national-security program in 1958, and its institutional descendants—National Resource Centers and FLAS fellowships—still anchor US capacity in less-commonly-taught languages and regional expertise. The scale is modest by defense standards, but the design logic is the same: markets undersupply slow-burn expertise, so the state tops it up. Contemporary rulemaking in 2024 even modernized NRC/FLAS regulations, a reminder that Washington intends to keep this architecture tuned. Suppose we continue to debate whether public funding “politicizes” area studies. In that case, we will miss the fundamental policy question: how to fund it legitimately, with guardrails strong enough to prevent capture but flexible enough to meet real strategic needs. This flexibility in funding is crucial to meet the ever-changing strategic needs.

Follow the Money: Public Financing and Empire Logics

When private donors and firms look at area studies, they see weak private returns: long language ramps, uncertain IP, and outputs that are public goods. States, by contrast, see option value—fewer surprises abroad, better crisis sensemaking, smoother commercial diplomacy. That is why the US system still invests $86 million in FY2024 across Title VI programs, even after the post-2011 contractions that scholars lament. It is also why advocacy groups and research universities pressed back in 2024 when regulatory changes risked weakening center capacities. The lesson is not ideological but structural: where outputs are public goods, public finance is destiny.

China’s finance is more comprehensive and directive. Consider the China Scholarship Council’s “country and regional research talent” program. It openly prioritizes Belt and Road–related countries, funds outbound fieldwork and degrees, and requires applicants to affirm political criteria—including support for Party leadership—alongside research merit. Layered atop this are MOE guidance documents (2015 onward) that set up base cultivation mechanisms and a 2017 push to register centers nationwide. None of these is subtle; all of them are coherent. The field’s expansion is not only about more scholars; it is about building a commendable network that can service ministries, SOEs, and provincial governments on demand.

Counting the New Architecture: Centers, Degrees, and Demand

We can measure the build-out, albeit with imperfect data. In 2017, official notices counted 395 research centers and 42 training bases. A scholarly survey in 2022 described 400+ university area-research institutions, consistent with only modest expansion from the 2017 baseline but with disciplinary elevation the following year. Because center registries are fragmented across ministerial and provincial levels, a precise 2025 figure is elusive. A transparent estimate, extrapolating a conservative 2–5 percent annual net growth post-2017 and accounting for consolidations, would place today’s number between 450 and 550 centers. That range is methodologically cautious: it uses observed 2017 counts as the floor, adds known 2022 discipline elevation as a growth shock, and assumes low attrition given political tailwinds. The estimate is not a boast; it is a planning figure for understanding the scale at which policy now interlocks with academe.

On the US side, 98 National Resource Centers were funded in FY2022, with the NRC line appropriated at $25.56 million and Title VI totals around $75.4–86 million in recent cycles when combined with FLAS and allied programs. The numbers are smaller than China’s center counts. Still, the unit function differs: NRCs are national resources for outreach and advanced language training, while Chinese centers are often policy-consulting nodes embedded in party-university ecosystems. In both systems, however, the growth signal is clear: geopolitical competition pushes states to bank expertise. What remains uncertain is the governance: who sets research agendas, who controls fieldwork risk, and what insulation exists between money and method.

Labor Markets and the Policy Use-Case

Skeptics often argue that area studies seats students in low-demand fields. China’s recent graduate market reminds us that the picture is more contingent. In 2025, the country expects 12.22 million new college graduates, which will intensify competition. Urban youth unemployment peaked at 21.3 percent in mid-2023 before methodological changes; under such pressure, graduates tilt toward state-sector roles and SOEs that prize policy-relevant language and regional competencies. Evidence from Chinese graduate surveys shows strong preferences for state employment, and reporting on elite campuses documents degree inflation into master’s programs as a labor-market filter. In that context, area studies’ public-sector alignment is not a bug; it is the employment pathway that exists.

The American labor channel is quieter but similar. FLAS fellowships and NRC ecosystems function as employment pipelines into government, nonprofit, and education sectors where public missions dominate and margins are thin. When federal funding dips, the market does not rush in; programs shrink, languages vanish from catalogs, and analytic depth erodes. That is the real opportunity cost of treating area studies as a luxury: in crises—from evacuations to sanctions design—the state rediscovers that it needs analysts who already know the files and speak the languages. The time to cultivate that bench is before the crisis, not after.

The Governance Problem: Funding Without Suffocation

The policy challenge is to recognize that instrumental value does not license ideological capture. China’s universities face intensified ideological oversight. Mandated ideology courses have expanded; researchers describe a turn toward insularity and new controls on international collaboration; student reporting suggests propaganda courses are widely disliked even as they proliferate. These dynamics will not stop the build-out of area studies, but they will think the knowledge if fieldwork is chilled and critical voices self-censor. The short-run effect is quietism; the long-run cost is shallower statecraft. A governance framework that protects fieldwork, allows plural methods, and separates budget authorization from research line-item control would buy China better knowledge even on its terms.

Democracies need guardrails, too. US Title VI centers are perennial targets in budget skirmishes; advocacy letters and rulemaking debates show how quickly politics can skew evaluation criteria or stigmatize regions. The fix is not to depoliticize the impossible but to proceduralize the inevitable: multi-agency cost sharing that prevents single-desk vetoes; rotation of peer-review panels to blunt ideological capture; transparent post-grant audits that track actual public value (graduates in public service, language proficiency outcomes, timely policy briefs). In both systems, the same principle applies: money may be public, but the method must remain scholarly.

Anticipating the Critics

One objection says that in the big-data era, translation engines and open-source feeds make area studies quaint. This misunderstands what the field does. It is not a dictionary service but a context engine—the habit of reading documents against institutions, incentives, and history. Data without context decays into pattern hallucination. The persistence of NRC/FLAS funding and the renewed regulatory attention in 2024 are tacit acknowledgments that governments cannot outsource situated judgment to APIs. What algorithms accelerate, area studies interpret.

A different objection insists that state funding turns scholars into propagandists. Here, the China–US contrast is real but not dispositive. China’s CSC criteria and ideological guidance are explicit and compulsory; the US Title VI architecture, while strategic, is pluralistic by design, with peer review, diverse regional representation, and public reporting. The correct answer is not purity politics but institutional design: security system directors from line ministries; shelter fieldwork under non-security umbrellas; publish negative findings; and require mixed-methods literacy to prevent monocultures that flatter funders. The point is to accept the strategic rationale for area studies while refusing epistemic monocropping.

Policy To-Dos: Building Capacity, We Can Trust

First, treat area studies as a knowledge infrastructure and fund it accordingly. In China, formal discipline status should be matched with fieldwork protections—simple measures like indemnity pools, transparent IRB processes for politically sensitive topics, and ministerial guarantees against punitive retaliation for good-faith research. Without this, the discipline will remain performative rather than analytic. In the United States, double down on counter-cyclical appropriations: when crises are quiet, keep the pipeline full; when they spike, resist faddish reallocation. NRC/FLAS is small enough to insulate culture wars while still changing outcomes.

Second, link funding to public, auditable outputs—not slogans. Require that centers publish annual language proficiency distributions; catalog fieldwork days; and archive policy memos with declassification clocks. Third, incentivize joint cross-border labs where feasible. Even amid rivalry, research on non-sensitive domains—public health surveillance methods, energy market data standards, archival digitization—can be pursued in sandboxed collaborations that raise global capacity. Fourth, build career bridges that make graduates legible to employers: standardized micro-credentials in translation for diplomacy, regulatory impact analysis, and sanctions design would convert general area knowledge into specific competencies. Finally, anchor governance in independent peer communities—professional associations and journals with diverse editorial boards—so that research quality, not political favor, structures recognition.

Back to the Number, and the Choice

The figure that initiated this discussion—395 centers and 42 bases listed in China’s records in 2017, with official discipline enhancement occurring in 2022—wasn’t merely intriguing. It served as a guiding framework. It conveyed that governments support what the market fails to provide and that area studies expand as empires grow. The United States’ Title VI funding line, consistent yet modest, communicates a similar message in a subtler tone. The allure of the policy is to debate its purity. The policy's essential goal is to formulate agreements that seriously consider strategy while safeguarding independence, as expertise becomes stale without it. Establish the framework. Release the assessments. Safeguard the fieldwork. Allow methods, not administrative bodies, to shape conclusions. If we accomplish this, area studies will continue to be what the present situation necessitates: a public good in a perilous world, funded by the government but operated for the citizens—a discipline driven by understanding, not rhetoric, able to convey truths that those in power must hear, even if they are reluctant to accept them.

The original article was authored by Els van Dongen, an Associate Professor at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. The English version of the article, titled "Area studies gain ground in China’s educational institutions," was published by East Asia Forum. For more information about SIAI’s Gordon School of Business and Artificial Intelligence, please visit https://gsb.siai.org.

References

AAU (Association of American Universities). (2024, March 26). AAU joins letter opposing proposed rule changes to NRC and FLAS.

CECC (Congressional-Executive Commission on China). (2024, December 8). Annual Report 2024.

Department of Education, US (2024). History of Title VI and Fulbright-Hays Programs.

Department of Education, US (2024). National Resource Centers (NRC) Program page and FY2022 awards.

Diplomat, The. (2024, June 22). Xi Jinping’s ideologization of the Chinese academy.

East Asia Forum. (2025, August 16). Area studies gain ground in China’s educational institutions (2017 counts cited; recent trajectory).

Foreign Exchanges (Thurston, A.). (2025, June 3). The decline and fall of area studies.

Financial Times. (2024, October 2024). ‘Too boring’: Chinese students are sleeping through propaganda classes.

Georgetown CSET. (2025, August 13). Outline of the Plan for the Construction of China into an Education Powerhouse (2024–2035) (translation/excerpt).

MOE, People’s Republic of China. (2015, January 26). Interim measures for cultivating and building national and regional study bases.

MOE, People’s Republic of China. (2017, March 14). Notice on 2017 work for country and regional studies (with center registration guidance).

NAICU (National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities). (2024). International education funding brief—FY2024 (Title VI total ~$86M).

People’s Daily/People.com.cn. (2023, April 11). Responding to the call of the times, area/country studies has great promise (recognizing 2022 discipline elevation).

ResearchGate (Fan, L., & Li, J.). (2022/2023). General Situation and Challenges of the Education of Area Studies as a Discipline in China (claims 400+ institutions by 2022).

Reuters. (2024, November 14). Record number of college graduates in China in 2025 (12.22m).

US Federal Register. (2024, August 27). NRC and FLAS Programs—Final Rule (program purposes and governance).

VOA News. (2021, August 25). China’s new mandatory curriculum focuses on “Xi Thought.”

Washington Post. (2025, July 13). In China, the expert’s is the new bachelor’s (youth unemployment context).

Xinhua/SCIO (State Council Information Office). (2016). Xi’s speech emphasizing philosophy and social sciences with Chinese characteristics (summaries).

XLS registry link (Gov.cn). (2017). Compiled registration form for MOE country and regional study centers (archival).

Comment